8. Belonging & Intersectionality

Belonging & Intersectionality

Everything is about relationships. What people think about, how they learn, what motivates them, how they stay engaged, how they perform, what they give up, and what they stand for can all be related back to interpersonal relationships, how a person was socialized, and whose voice is the most acknowledged within a given relationship. How a person makes another person feel is based on intentionality and forms the basis for belonging.

Understanding racism and other systems of inequality are critical for the workplace to function optimally, especially postpandemic. In a survey of 2,000 employees, almost half (43%) said they are looking for a new job, and corporate culture was the main reason. When probed further about corporate culture being the main reason, participants indicated that a lack of corporate equity and fairness accounted for more than three quarters (77%) of their easoning. Furthermore, 92% of employees said they would be more likely to stay with their job if their bosses would show more empathy. Finally, engaged employees are 59% less likely to seek out a new job or career in the next 12 months.41 The problem for most organizations is that they cannot change what they do not know and have not sought to understand. When employees seek more empathy, their identities and experiences are also on the forefront. Empathy ultimately leads to a greater sense of wellbeing due to feeling included, acknowledged, and valued. However, empathy cannot be felt if the person who it needs to come from does not understand or acknowledge how a person’s identities and experiences are affecting the situation.

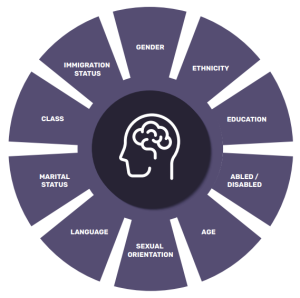

Intersectionality is a term introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 to describe how race, class, gender, and other salient identities “intersect” with one another and overlap. Figure 3. An Example of Intersectionality shows how the multiple identities intersect.

These intersections of personal identities create discrepancies and inequity in legal rulings as well as within the talent pipeline. Crenshaw indicates that intersectionality is an analytic that helps people think about identities in a holistic perspective, as well as who has the power in a given situation.42 From the context of interpersonal relationships, intersectionality helps explain systemic oppression because it demonstrates how the cycles of socialization have upheld who is deemed of higher importance. Simply put, it indicates whose voice is most listened to and valued, in any given relationship. The person who’s voice is most listened to and “valued”, is the person who holds the power, and ultimately makes the decisions and controls the outcomes for those within the relationship, regardless of whether it is fair or empathetic. This lens allows people to see that inequality is not simply individual bias or behaviour, but a consequence of deeply embedded practices, collective intentionality, diversity blindness, organizational hierarchies, and systemic oppression.43 For leaders to become more empathetic, emotionally intelligent, and create a belonging-first culture, intersectionality must be understood and applied.

While this list of questions is simply an introduction to generate initial insights, the intentionality of learning, understanding, and furthering them supports leaders in their ability to start building the next generation of workers and leadership. At the heart of a leader’s legacy lies their ability to perform a systemic analysis fostering the required systemic changes.

The following questions are important for organizational leaders and organizational members to ask while re-imagining a new normal:

- What are the historical, social, economic, and political realities that are affecting this person in this situation?

- What toll have these factors had on people’s bodies, mental health, and cognitive capabilities?

- How are larger societal forces affecting people’s experiences, perceptions, and behaviours?

- What societal forces are affecting perceptions of equity, diversity inclusion, and belonging?

- Who has the opportunity, access to resources, and embedded belonging without having to prove value, skill, or capability?